If we winter this one out

we can summer anywhere

Seamus Heaney

Essay

COVID-19 is neither the first pandemic the world has faced - nor will it most surely be the last. Are there lessons to be identified - or even learned - from pandemics past?

This by no means is to convey that nothing can be learned from pandemics past, patterns do not repeat themselves, or they hold no understanding worth recollecting. A recurring feature, when looking at pandemics in plural, seems to be that a pandemic emerges inconveniently, is often recognized belatedly, can manifest itself in many ways, challenges systems and prevailing notions and does not just happen; often it is allowed to happen. Science will to a large extent be able to tell what should be done, while politics - the art of the possible - Attributed Otto von Bismarck (1815-98), German statesman as always determines the framework of what is feasible to do.

The risk of relying too heavily on the uniformity of pandemics is, with an expression from Italian author and semiotician Umberto Eco, to become a victim of your own background books; past reading has a tendency to tell us what we are supposed to discover. In an essay, From Marco Poli to Leibnitz: Stories of Intellectual Misunderstandings i Serendipities: Language and Lunacy, Harvest, 1999 Eco tells the story of Marco Polo and the unicorn. Marco Polo grew up in a tradition where people were convinced unicorns existed. So when, on his way home from China, during a stay in Java, he is introduced to an animal with a single horn on its muzzle, there is no doubt in his mind that what he sees is a unicorn. However, he notes that the Java unicorn is not the gentle beast otherwise associated with unicorns. The creature is neither white nor resembles a horse, but is black with pelt like a buffalo, hooves as large as elephants and the head looks like a wild boar. Had it been recognized in Marco Polo's time, one might get the idea that it was a Java-rhinoceroswhich has a single horn. The Sumatra rhinoceros and the African rhinoceros both have two horns Java rhinoceros he saw ...

On the other hand having no experience to draw upon would leave you in a bad place. Past experiences are helpful when facing obstacles - and also, hopefully, ensure the same mistakes are not made too often. But relying on experience must, of course, be handled with care. When faced with something really new, where experience have little value, the risk is inaction. Or that well-known models are pressed upon the new, regardless of fit.

If the outbreak is not controlled or dwindles by itself, but continues to grow, the next step is an epidemic, which denotes a growing number of cases in a particular population group, within a certain period of time.

A pandemic refers to an epidemic on several continents simultaneously.

A global pandemic, a pandemic on all continents at once, is a

double pleonasm. Nevertheless, the WHO and the EU began using the

term during COVID-19COrona VIrus Disease

2019 to signal that a global

pandemic Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus & Ursula

von der Leyen in The Telegraph 30. september 2020  requires a global and coordinated effort.

requires a global and coordinated effort.

In my time, i.e. since 1953, there have been a number of disease outbreaks that meet the definition of a pandemic: a new or re-emerging, contagious disease against which the population has no natural immunity, which is spreading across several continents and which has serious consequences

| Asian flu | H2N2 | 1957-58 |

| The Seventh Cholera Pandemic | El Tor | 1961-75 |

| Hong Kong flu | H3N1 | 1968-70 |

| Russian flu | H1N1 | 1977-79 |

| AIDS | HIV | 1981- |

| SARS | SARS-CoV1 | 2002-04 |

| Swine flu | H1N1/09 | 2009-10 |

| MERS | MERS-CoV | 2012 |

| West African Ebola | EBOV | 2013-16 |

| Zika | ZIKV | 2015-16 |

| COVID-19 | SARS-CoV2 | 2019 |

Compared to the flu pandemics and AIDS, SARSSevere

Acute

Respiratory Syndrome was modest in scope, but

because an unreported outbreak in China soon became the first

pandemic in a globalized world, WHO found it necessary to expand

the typologi. With the adoption of the International

Health

Regulations

Can be downloaded via who.int  in 2005, a PHEIC - Public Health Emergency of

International Concern was introduced and defined as:

in 2005, a PHEIC - Public Health Emergency of

International Concern was introduced and defined as:

"an extraordinary event which is determined to constitute a public health risk to other States through the international spread of disease and to potentially require a coordinated international response".

An international, ad hoc expert committee advises the Director - General of WHO on whether a PHEIC - above epidemic, below pandemic - should be declared. It has been the case

| Swine flu | 2009 |

| Polio in Afghanistan, Pakistan & Nigeria | 2014 |

| West African Ebola | 2014 |

| Zika | 2016 |

| Kivu Ebola in DR Congo | 2019-20 |

| COVID-19 | 2019 |

In many ways, the PHEIC of Public Health equals SecuritizationConcept developed at the Copenhagen School of security studies by Ole Wæver of International Relations; both legitimize the use of extraordinary means to solve a perceived problem. But for a PHEIC - and securitization - to work, it has to be taken seriously. When WHO on January 30, 2020, declared COVID19 a PHEIC, nothing much happened. Too many of the political leaders, who took action when the West African Ebola was declared a PHEIC in 2014, were no longer in office and their successors did not have the same perception of a threat. Which may help explain why global pandemic became part of the political vocabulary.

Another difficulty with the PHEIC definition is seen in the absence of MERSMiddle East Respiratory Syndrome on the PHEIC list, while on the list of pandemics. MERS, which is also caused by a coronavirus, was first detected in Saudi Arabia and has since spread to more than 24 countries. But the question with MERS was whether the extraordinary measures, a PHEIC could legitimize, would solve anything, because the vast majority of cases were nosocomial infections - rather than persistent societal spread. If the outbreak could be curbed by improved hospital hygiene, it might be overdoing it to declare a PHEIC. On the other hand, it can also be seen as an illustration of the inability of the WHO system. For a PHEIC in the case of MERS would mean that Saudi Arabia could be visited by international inspectors and forced to hand over data. Which would require Saudi Arabia to consent.

Anne Brockenhuus-Schack & Poul Birch Eriksen: AIDS -

mellem linjerne.

Sommer & Sørensen. 1988 from my coverage

since the mid 80s as a special correspondent for the public Danish

Radio.

Although drawing parallels between pandemics have to be done with some care, it seems to be a common trait that the emergence of a pandemic rarely is convenient. Perhaps particuarly to those, who have to deal with it. They are not sitting idle, waiting for it, but have busy schedules, filled with often quite sensible chores, making it difficult to pick up signs that something is afoot.

Halfdan Mahler, WHO Director-General 1973-88, said on several occasions towards the end of his term that the World Health Organization was asleep at the wheel, when AIDS emerged.

Among other things because focus was on the Alma Ata Declaration

Health for All by the Year 2000, Can be downloaded as pdf via who.int  adopted in 1979 and to be implemented in the

years thereafter.

adopted in 1979 and to be implemented in the

years thereafter.

But also because the infectious disease AIDS emerged at a time when it was being considered whether infectious diseases were becoming a thing of the past; due to better prevention and hygiene, improved living conditions and living standards, antibiotics and smallpox being declared eradicated by WHO in 1980, thanks to a targeted vaccination campaign.

What understandably led to discussions whether resources in light

of this Epidemiologic Transition Concept outlined by Abdel R. Omran in The

Epidemiologic Transition: A Theory of the Epidemiology of

Population Change

The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, Vol. 49, No. 4, Pt. 1,

1971 (pp. 509–38)  should

be directed more towards major killers such as cancer and

cardiovascular disease.

should

be directed more towards major killers such as cancer and

cardiovascular disease.

And was also reflected in considerations like those at Aarhus University, where a chair in epidemic diseases was left vacant in the early 80s, as there were doubts if it should be upheld. Eventually, it ended up as a chair in tropical medicine.

The first mention of AIDS in the medical literature was a case

study report from Los Angeles of five gay men in their 30s with

symptoms inconcurrent with their age group, published in CDC's

WMMR Weekly Morbidity and Mortality Report  on June 5, 1981.

on June 5, 1981.

A case study report not only is a doctor's way of presenting an observed, unusual medical history via a professional journal, but also poses an implicit question to medical community at large: anyone seen something similar? The report in WMMR soon led to responses from other doctors, elsewhere in the United States, about other gay patients with atypical symptoms. From here it was not far to equate the new disease with gay men.

Which for many reasons was inconvenient for the gays. By 1974, homosexuality had been removed from the list of mental illnesses with the publication of the American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, sixth edition of the DSM-II. The Danish National Board of Health followed suit in 1981 and WHO in 1990 with the adoption of ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases; a work that had begun in 1983. Hardly had one disease label been removed from being gay before another was ready to replace it.

The initial, close link between AIDS and gay men provided a skewed starting point. Not only did it make AIDS appear to be a sexually transmitted disease; it was furthermore homosexually transmitted. As it did not fit well with the value politics of the 80s, the disease was ignored politically, at least as long as it 'only' affected a minority with a lifestyle too different. This is one of the explanations for the lack of research funding. But also from the research side no great prestige was seen in a sexually transmitted disease affecting marginalized groups.

It is a little more complicated with infectious diseases. The first piece that needs to fall into place is that one should be aware, not just of something unusual going on, but also have an idea of what to look for.

The five Los Angeles medical histories described in the WMMR on June 5, 1981, were by no means the world's first AIDS case. But it was the first time in a limited geographical space - three hospitals in Los Angeles - patients were observed with Pneumocystis carinii, a pneumonia they were not supposed to have. That report led to feedback from other doctors with similar patients, although they had not (yet) reported them. Who not only had the special form of pneumonia, but also other unusual diseases - opportunistic infections otherwise only seen when the immune system is weakened.

And then it could easily have gone worse. American epidemiologist Jonathan Mann first head of WHO's Global Programme on AIDS, 1986-90 outlined a thought experiment in the preface to Laurie Garrett's The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance, Penguin 1995 to show how 'lucky' the world had been to discover AIDS in 1981. A single or all of the following 'ifs' could have postponed the recognition another 5-10 years:

- if the immunodeficieficy of AIDS resulted in an increase of more typical infections rather than the easily recognized, unusual opportunistic infections (Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia) or cancers (Kaposis sarkom);

- if AIDS had not clustered among active, self-identified gay men, but rather had been spread more broadly within society;

- if AIDS had not occurred in a country (U.S.A.) with a highly developed disease surveillance system, capable of linking reports of cases from many different geographical areas;

- and if the science of human retrovirology had not been recently developed, including techniques for detection.

A crucial factor in any infectious disease is the time that elapses from infection until symptoms appear. With flu, the incubation period is a few days. With COVID 1-2 weeks. With AIDS several years. A pandemic may only be recognised, once disease stage is reached. A widely used illustration of the AIDS pandemic has been icebergs or hippos, because the sick, who caused the attention, actually only corresponded to what protrudes above water. What was below water surface was murky, but extensive due to the long incubation time.

When it comes to influenza and respiratory infections, making sense of symptoms can be intricate. How do you know, when seeing the first flu case of the season whether it is a common flu or something worse? With AIDS, comorbidities were hard to miss because they were so unusual. Especially when so many cases seemed to be found among men who had sex with men. It made connecting the dots and seeing a pattern easier. The down side, however, was that the overwhelming number of gays with complicated diseases made it difficult to see an even bigger picture: that AIDS was an infectious disease that, given the right conditions, could have a much wider impact.

The importance of good disease surveillance is perhaps best illustrated by a counter-story: When the first cases of Ebola emerged in late 2013 in the border area between Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, it was something of a question whether the cases were reported, where to and whom - if anyone - had an overview? A very distinct feature of West African Ebola was the emergence in West Africa; a area with hitherto no hands-on experience with the disease. All outbreaks since 1976 had taken place in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in Uganda, where routines for control and containment had gradually been incorporated - centrally and locally.

However, despite good disease surveillance, there are still problems with a newly emerged disease, because it requires data from many patients to get answers to a wide range of questions of importance to intervention: How long is the incubation period? How contagious is it? How many are asymptomatic carriers? How pathogenic is it? How deadly is it? What are the routes of infection?

In many crisis, early, but far-reaching decisions are often made when evidence is sketchy, at best. In the hope of said intervention decisions will be adjusted, once more knowledge is assembled.

At the same time, one must constantly assess whether the driving force in the spread of the infection is something inherent in the virus? Or human behavior? Whether the spread is something that just happens - or something that is allowed to happen.

Even with seasonal flu, where the incubation period is known and there is an empirical presumption as to how many asymptomatic and mild cases can spread the virus, it can be difficult to quantify infectiousness, how disease-causing it is and how many of the diagnosed will die, before a certain number of patients have been seen. During a seasonal flu, about 0.002 percent of those diagnosed die - although the number may vary from year to year - while for pandemic influenzas it has been around 0.1 per cent - with the Spanish Flu (1918-20) as the outlier with over 2.5 per cent.

In comparison, the mortality rate for untreated AIDS is 100 per cent, Ebola 80-90 per cent. MERS 35 pct. and SARS 11 per cent.

As Jonathan Mann writes, it was fortunate that prior to AIDS, scientists had become interested in retroviruses, to which HIV and hepatitis B belong. Nevertheless, it took a relatively long time, until December 1983, before HIV was identified and it became possible to screen blood samples for infection.

In a world where the craft of medicine has increasingly become synonymous with treatment, surgical or medical, there seem to be a tendency to overlook other facets of the craft like prevention and diagnostics.

Although Ebola has been known since 1976, it took a full three

months from the first known case of the West African outbreak in

December 2013 until the virus was identified with certainty.

Subsequent analyzes of the outbreak Kelly-Cirino CD, Nkengasong J, Kettler H, et

al Importance of diagnostics in epidemic and pandemic

preparedness BMJ Global Health 2019;4:e001179.  suggest

that if 60 percent of the patients had been diagnosed within one

day, instead of five, the further spread of infection would have

been significantly reduced. What more than anything got the

outbreak contained was when diagnostic information became the

guideline for appropriate intervention. The unprecedented scale

of the West African Ebola pandemic set in motion research that

could move from traditional viral culture techniques and electron

microscopy to faster, more accurate molecular analyzes that could

be applied decentrally, closer to patients. However, it is an

open question how important these new methods were in the Ebola

outbreak in April 2018 in the province of North Kivu in the

Democratic Republic of Congo. But it was probably mostly due to

the fact that the outbreak took place in a civil war zone.

suggest

that if 60 percent of the patients had been diagnosed within one

day, instead of five, the further spread of infection would have

been significantly reduced. What more than anything got the

outbreak contained was when diagnostic information became the

guideline for appropriate intervention. The unprecedented scale

of the West African Ebola pandemic set in motion research that

could move from traditional viral culture techniques and electron

microscopy to faster, more accurate molecular analyzes that could

be applied decentrally, closer to patients. However, it is an

open question how important these new methods were in the Ebola

outbreak in April 2018 in the province of North Kivu in the

Democratic Republic of Congo. But it was probably mostly due to

the fact that the outbreak took place in a civil war zone.

AIDS is and has been a problem among IVDUintravenous drug user s, but not necessarily universally. In the Scottish capital Edinburgh it became a huge problem in the 80s with over half of the city's injecting drug users infected; in Scotland's largest city Glasgow, 70 kilometers to the West, a minor; and in Newcastle, some 150 kilometers to the South, hardly a problem at all. In all three cities, heroin was cheap at the time, but the difference was that the Edinburgh police, as part of a zero-tolerance policy towards the drug use, confiscated all works they could, while at the same time made it difficult to procure new syringes. This forced the injecting drug community to not only share works, but also reuse injection needles that were meant to be disposable. In Glasgow, authorities were nowhere near as restrictive, and although AIDS was found among the city's IVDUs, it was on a much smaller scale. In 2014, though, Glasgow did experience a major outbreak, among the city's drug users, many of whom were homeless.

As for Newcastle, chasing the dragon, i.e. smoking, was the preferred way of taking heroin. Since inhaling does not involve the use of injection needles, transmission through the blood veins became nothing to worry about.

A Dutch harm reduction researcher Janhuib Blans once put it: an intervention that works in Amsterdam does not necessarily work in Rotterdam, 60 kilometers apart - and vice versa.

In the early days of the AIDS pandemic, where only cases among gays had been seen, some in the United States began pondering whether it could be a 'device error' - something gays did or something they ingested that was produced incorrectly. Suspicion focused mainly on Poppers, amyl nitrite inhalants, that were popular to sniff as a sex stimulant The fascinating thing about this - rather American - approach is that a solution will be both simple and cheap - especially compared to the much more burdensome and expensive investigation of a new disease's transmission routes. However, the hypothesis could not be corroborated by the data collected.

A variant of the device error thinking has also had its proponents under COVID-19, namely the notion of a quick fix. And by extension, if a partial solution does not solve the whole problem, does it then work at all? As was evident, for example, from the discussions about facemasks. Does it protect at all? And who does it protect? How? Is it the wearer from becoming infected. Or does it make it harder for the wearer to pass infection on? Does it protect if the fit is not tight? If the nose is free?

On the whole, simple, elegant solutions to curb infectious diseases are indeed rare. Rather a combination of a series of, often well-tried, low-practice measures. Which, seen individually, may not make the big difference, but do precisely that in unison.

AIDS is a syndrome, a disease picture of several different symptoms, caused by the underlying immune deficiency. Although it was known from diseases such as tuberculosis that a combination of treatments has merits, it took a long time before the concept was transferred to AIDS.

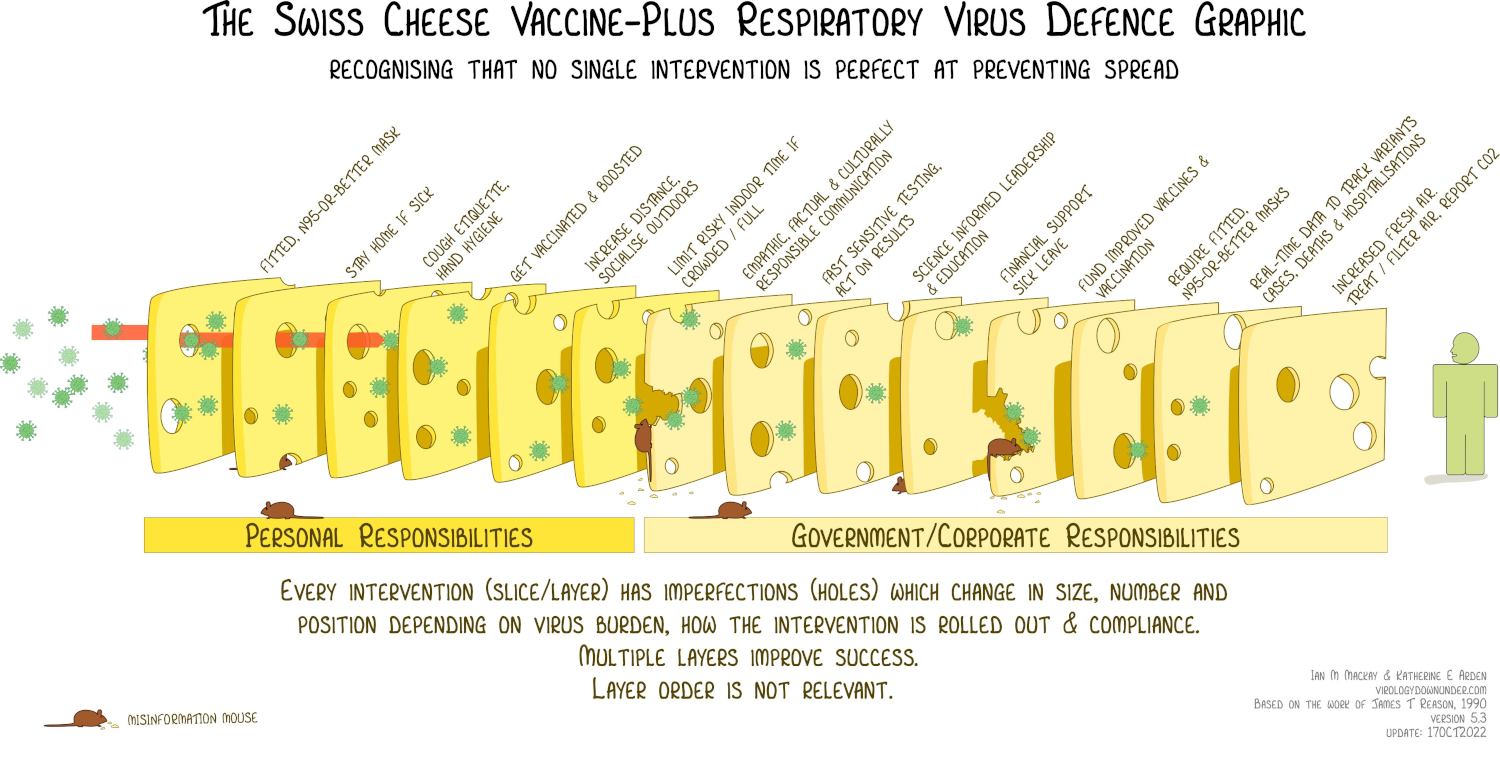

For COVID-19, Australian virologist Ian M

MacKay The

blog Virology Down Under  of Queensland University has reworked the so-called Swiss cheese

model of riskreduction, originally developed for risk analysis and

management, based on research into disasters of the 80s such as Bhopalgas leak explosion at the Union Carbide

pesticide plant in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India, 1984. ,

ChallengerSpace Shuttle fatal accident,

off the coast of Florida, USA, 1986 and Chernobylnuclear

accident in Ukraine, Soviet Union, 1986 by James T. Reason The contribution of latent human failures to

the breakdown of complex systems Philosophical Transactions

of the Royal Society B, 1990

of Queensland University has reworked the so-called Swiss cheese

model of riskreduction, originally developed for risk analysis and

management, based on research into disasters of the 80s such as Bhopalgas leak explosion at the Union Carbide

pesticide plant in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India, 1984. ,

ChallengerSpace Shuttle fatal accident,

off the coast of Florida, USA, 1986 and Chernobylnuclear

accident in Ukraine, Soviet Union, 1986 by James T. Reason The contribution of latent human failures to

the breakdown of complex systems Philosophical Transactions

of the Royal Society B, 1990  of University of Manchester. The idea is that protection is

achieved through not a single layer but a series of layers. If a

layer is seen as a slice of Swiss cheese, with its characteristic

holes, it becomes easily understandable why not to rely on the

perfection of a single layer. If furthermore the holes aligns, the

risk of something going wrong increases; hence multiple slices,

layer upon layer, reduces the overall risk.

of University of Manchester. The idea is that protection is

achieved through not a single layer but a series of layers. If a

layer is seen as a slice of Swiss cheese, with its characteristic

holes, it becomes easily understandable why not to rely on the

perfection of a single layer. If furthermore the holes aligns, the

risk of something going wrong increases; hence multiple slices,

layer upon layer, reduces the overall risk.

The clever thing, worth noting about Ian M MacKay's COVID-19 adaptation is that some of the slices are personal responsibilities - physical distancing, use facemask in places where distance can not be kept, hand hygiene - whereas others are shared - proper ventilation in public spaces, create opportunities for hotel quarantine, restrict travel abroad, provide relief packages, vaccines. And do note the mouse, representing misinformation.

As COVID-19 has progressed, public understanding seems to have had a hard time getting its head around that it is not the individual layer but the combination that makes the difference. Not just in relation to COVID-19, because the layered risk reduction has had a secondary effect: Almost no flu in the 2020-21 season.

Untangling one of the key chains of transmission is quite telling: the very first cases of SARS were seen in November 2002 in China's Guangdong province. The Chinese authorities tried to contain the outbreak locally and saw no reason to involve WHO. A symptom-free Chinese doctor, who had treated SARS patients at a hospital in the metropolis of Guangzhou, traveled to attend a family wedding in Hong Kong, 130 kilometers away, and ckecked in at the Hotel Metropole's ninth floor on February 21, 2003. Here he fell ill, was admitted to a Hong Kong hospital and died in early March.

At least 16 hotel guests from the same floor became infected and unknowingly spread the infection by plane to Vietnam and Canada, among other places.

One guest, who had stayed on Hotel Metropole's ninth floor, an American businessman, flew to Hanoi, where he fell ill and was admitted to the city's French Hospital on February 26. It was from here WHO for the first time was notified of a new form of severe pneumonia. The businessman was evacuated back to Hong Kong, where he died March 13.

Another ninth-floor hotel guest traveled to Toronto, Canada,

where the first case was registered on February 23. The woman in

question died in her home on March 5.

She had infected her son, who was admitted to one of the city's

hospitals, where he died on March 13.

Here he infected other patients, hospitalized for other reasons.

To avoid congestion in a single hospital, the infected patients

were distributed to other of the city's hospitals.

In Toronto, as in so many other places, dealing with highly

contagious diseases was no longer part of daily hospital routine.

This meant i.a. that all patients entered and exited the same main

entrance and were taken up and down the centrally placed

elevators of the high-rise. Add to that the fact that the

protective equipment was deficient, as were knowledge of its use.

As a result, many health care workers became infected.

A total of 257 cases were registered in the province of Ontario

in a chain of transmission that could be traced back to the ninth

floor of the Hotel Metropole in Hong Kong.

One obvious lesson from SARS, which was declared contained on 5

July 2003, was the lack of early warning. And of contingency

plans. In connection with the adoption of the International Health

Regulations in 2005, a WHO expert group had prepared a plan

World

Health Organization: WHO global influenza preparedness plan

: the role of WHO and recommendations for national measures

before and during pandemics. 2005

Can be downloaded via who.int  that became a template for national

preparedness plans.see

for example the Danish "Beredskab for pandemisk influenza,

del I": National strategi og fagligt grundlag. 2013

that became a template for national

preparedness plans.see

for example the Danish "Beredskab for pandemisk influenza,

del I": National strategi og fagligt grundlag. 2013

This is a revision after the 2009 pandemic

Can be downloaded via sst.dk

As is well known, predicting is difficult, especially about the

future, so the planners took quite a risk by assuming that the

next pandemic would be caused by a bird flu.H5N1

And that this zoonosis would originate in Southeast Asia, where

influenza tends to come from: not only do many people but also

many domestic animals share a relatively small area, the climate

provides favorable conditions for say an influenza to jump from

one species to another - and maybe back again. As a starting

point, both men and beasts can live in tolerable symbiosis with

the infection in question, but with replication comes a built-in

risk for mutation.Replication is a

prerequisite for mutations. If virus does not replicate, no

mutation.

Hence the concern about a continual spread of infection in 17

million Danish farmed mink Sometimes to a more

infectious variant. And/or more disease-causing variant. .

Add that there is no scientifically proven

theory Theobald Smith's (1859-1934) alledged "law of

declining virulence" - captivating as it may be - that host

and pathogen will develop a "mutually benign relationship"

over time, is but a hypothesis that never became a

scientific theory, backed by observations.

Current thinking is that each host-pathogen relationship

must be considered separately and that there is no general

pattern that predicts how each of these relationships will

develop on how outbreaks caused by mutations

develop. Some dwindle on their own, some can be controlled using

well-tested measures from the Public Health toolbox, as with SARS,

which faded over the course of one year. Others again prove to be

more difficult. Like HIV. Or TBTuberculosis

usually caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria,

which has been known for centuries. Not to mention dengue

fever mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by the

dengue virus, also known for centuries

Earliest record of a case of probable dengue fever is in a

medical encyclopedia from the Jin Dynasty (266–420),

which seems to have increased in virulence in recent decades.

The preparedness plan was done, dusted and ready to be executed when the next pandemic made itself known in 2009. But had to quickly realize the relevance of Prussian Field Marshal Helmuth von Molkte'sThe Elder dictum Kein Operationsplan reicht mit einiger Sicherheit über das erste Zusammentreffen mit der feindlichen Hauptmacht hinaus that no plan survives first contact with the enemy.

Firstly, it was a swine flu and not the anticipated bird flu. Secondly, it was first recognized in Mexico and not in Southeast Asia. Thirdly, it began in the northern hemisphere in Spring and not in Autumn as influenza tends.

However, these obstacles were no bigger than could be dealt with through improvisation - as has to be done in crisis management. But there were plenty of other developments to keep an eye on, because the new H1N1 outbreak - incidently, the same flu variant as during the Spanish Flu some 90 years before - was as infectious as predicted and had in just three months worked its way through the plan's six phases. As a logical consequence, the WHO declared a pandemic on 11 June 2009.

Here is the rub: the pandemic H1N1/09 virus was not particularly pathogenic, compared to a seasonal flu. What the plan had assumed to such a degree that no lever for adjusting had been buildt in: it could only act on number of cases, but not take severity of cases into account. A pandemic was declared, as prescribed by the plan, yet the many infected did not equal an overwhelmed health care system.

With SARS, as mentioned, an early warning system was dearly missed, as well as better access to and updated knowledge on the use of personal protective equipment. Not to mention clear guidelines for how to report unusual cases of disease, in a global world.

With AIDS, the overall problem was trying to solve a crisis as if nothing had happened. And when interventions finally got into gear, the overload of cases among gay men were so resource demanding, it was overlooked that others could also be at risk. What to some extent should have been known, since just a few years before AIDS a major outbreak of Hepatitis B had, via the very same transmission routes, in addition to gay men, also infected IVDUs, haemophiliacs and recipients of blood transfusions.

The blood supply should have been the aspect of the pandemic easiest to control, as it is directly regulated by government. Those in charge are usually doctors who, in theory at least, should be making decisions with a modicum of interest in their medical concequenses.Randy Shilts in the prefase to Anne Brockenhuus-Schack and Poul Birch Eriksen: AIDS - mellem linjerne. 1988 That did not happen and the inevitable tragedies of transmitting AIDS to hemophiliacs and transfusion recipients were not averted. As a consequence of these failings, seen with minor variation from country to country, the regulation of blood and the medicinal products that can be extracted from blood are no longer regulated by the individual member countries of the EU. Instead it is now part of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European UnionArticel 168 , which states that EU sets some very high minimum requirements for blood and blood products.

With AIDS, it was also a problem that the industrialized countries took a long time realizing that in Africa AIDS was a distinctly heterosexual disease. Like access to the expensive drugs. When they, at long last and overdue, became available, the question of access was framed as who could get them paid for in the insurance-based U.S. health care system. Only when that began to be resolved, attention was shifted to the poor countries of the world and their problems.

Another thing AIDS put its finger on was knowledge sharing and the complete dependence on printed scientific journals. After all, AIDS began before the Internet made it possible for journals to publish important articles online before printing. And before pre-print servers gave researchers the opportunity to upload their not yet peer-reviewed articles online.

With COVID-19, a host of other dormant issues have been uncovered. Like hospital services have eventually become so efficient that handling a larger crises may be difficult. Much can said for modern hospitals having a special ward, where others wards across speciality acutely can offload patients in need of intensive care. The prerequisite for an intensive care unit to handle this relief function is a large throughput.

The workings of the system are that as soon as the individual patient's crisis is over, the original ward again takes over the further treatment. But with COVID patients, the crisis and the need for continued intensive care can be long-lasting.

Weaknesses in elder care have also been exposed. Age is a

risk factor for COVID-19, but still cannot alone explain the

excess mortality among older citizens, as has been seen in among

others Canada André Picard: Neglected No

More: The Urgent Need to Improve the Lives of Canada's Elders

in the Wake of a Pandemic

Random House of Canada, 2021 and in Sweden.

Äldreomsorgen under pandemin - Elder Care

during the Pandemic

Can be downloaded as pdf via coranakommissionen.com

A thoroughly industrialized country like Germany has found itself lagging behind in terms of digitalisation. Local casereports and test results are collected by the central authority, the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin, from where data are made available online. But the feed happens via fax and a manual re-entry into the department's computer system.

COVID-19 has also led to the rediscovery of contact tracing, quarantine and One thing, though, seems to be a constant for pandemics: the longer one waits to intervene, the more draconian the interventions become.other traditional public health tools doubted to be of value in an increasingly individualized world.

Characteristic of COVID-19 - so far - has been a rather selective use of knowledge. Especially when talking the pandemic down. Like as said many times that most of the known, human coronaviruses only cause the common cold.Which in most cases is caused by rhinovirus, a different family to coronavirus To be translated as: this must also apply to the new. Or like when knowledge from, for example, the Spanish Flu is ignored: Just because one wave is over, the pandemic isn’t necessarily so.

In the times of COVID-19, the public health dilemma still applies:

- Act too slowly - and be criticized for not stopping preventable suffering and death

- Act aggressively and stop an outbreak in its infancy - and be accused of overreacting

Lessons must be identified before they can be learned from. There can be many reasons why it goes no further than identifying: the crisis is over, it went fairly well, the inbox have swelled while pandemicing and so on. Sometimes there are structurally built-in reasons why changes called for by lessons learned are difficult to implement. But once in a while one can not stop pondering if the built-in is a doing of a leading comrade, who currently can not be moved?

One thing, though, seems to be a constant for pandemics: the longer one waits to intervene, the more draconian the interventions become.